We made our own dance floors

In a new series of articles, Hana Flamm is diving into the history of Dublin’s queer bar scene from as early as 1973. Starting with the Viking Inn, hear from the patrons who organised, drank and danced in these pubs.

Map overleaf by Hana Flamm.

What was the first gay bar you ever visited? How did it feel to step inside?

For many queer people, the gay bar has been a place of freedom: a space to connect with others, somewhere to dress however one wants, to explore one’s identities. For others, gay bars have been exclusionary, unsafe, dirty, or stifling. For me, especially as a foreigner in a new town, gay bars have often been a way to find my local community— to meet lovers and friends; be in a space to engage with a shared history.

I distinctly remember my first time in Street 66 shortly after I moved to Dublin. I was awestruck by the bar population’s diversity. While the range of gender presentation and ethnicity was a welcome surprise, I was most surprised by the age diversity. Tables of 20-year-old men sat next to tables of 70-year-old women, and the bar featured significant proportions of all ages. Coming from the New York City queer scene, I had never seen such an age range in an LGBTQ+ venue before: in New York, gay and lesbian bars are largely gender-segregated, and bar visitors over the age of 35 are generally nowhere to be found.

Maybe the age diversity reflects the limited options Dublin offers its LGBTQ+ community. On the other hand, it likely reflects a culture that encourages older people to remain in the public and social sphere. In an era when gay bars are purportedly declining, considering their history feels important to me. Gay bars have been, and continue to be, places where queer people have found each other when no other options offered connection. Especially in Ireland, where the public house historically provided a central meeting point for local communities, the gay bar was a refuge when the local pub would have been unwelcoming, or even unsafe.

Over the course of three articles in GCN magazine, we will—figuratively—step into a few of Dublin’s queer venues that existed between 1973 and 1993, illuminating our shared history through the experiences of people who lived it. Many of these stories come from oral history interviews; those whose memories now actively share and shape portraits of Dublin’s former gay bars. The George, opened in 1985 and expanding twice to reach its size today, is the only surviving gay bar from the era. While a number of gay bars have opened and closed in Dublin throughout the years, the persistence of their existence reflects a community clamouring for a place to gather, party, explore, organise, and exist.

There have always been bars that Dublin’s LGBTQ+ community frequented, regardless of whether the proprietors claimed that status as a gay bar. By the 1960s, you might have found a gay customer base at bars near The Gaiety Theatre—most notably, Bartley Dunne’s, Rice’s, the Bailey, and Davy Byrnes (of Ulysses fame!). The most popular of the bunch was Bartley Dunne’s.

In a 1991 GCN article, Anthony Redmond reminisced that on Fridays and Saturdays, “the whole place was an exotic melange of colour and high camp”. Despite this flamboyant description, Bartley Dunne’s owners persistently denied that the bar hosted a gay clientele or was in any way a ‘gay bar’.

While many gay men enjoyed the scene as it was, a number of queer men and women sought to create a gay community and ‘come out’ as a public movement. The foundation of the Irish Gay Rights Movement (IGRM) in 1974 and the National Gay Federation (NGF)’s subsequent formation in 1978 encouraged visibility for gay men and women with the demand for decriminalisation and the formation of explicitly gay spaces. Each organisation opened its own community centre, both of which operated weekend discos. IGRM’s Phoenix Club on Parnell Square West and NGF’s Hirschfeld Centre at 10 Fownes Street offered spaces for Irish queers to meet one another and exist openly in their sexual and gender identities.

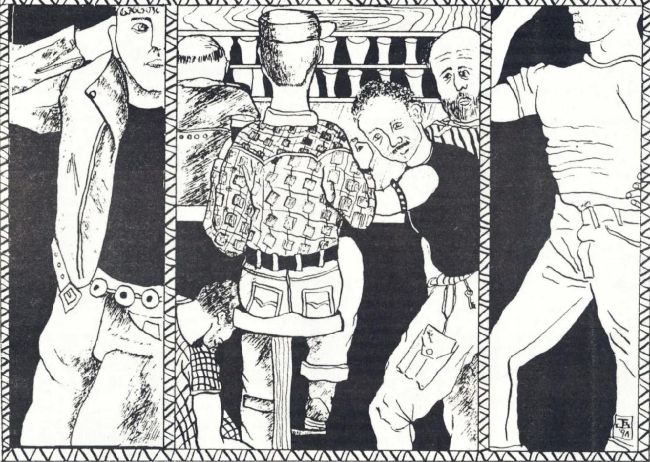

Illustration by John Byrne (GCN Issue 27, March 1991)

For many people, the Phoenix Club and the Hirschfeld Centre were intimidating, as stepping inside was an explicit statement of ‘coming out’. As Eamon Redmond recounted to GCN, “There was no escaping the knowledge of what went on in the building as the brass plaque clearly spelt out the name: Irish Gay Rights Movement.” Another Dubliner, Eoin, felt that he “couldn’t afford to go to the Hirschfeld Centre” because he couldn’t afford to be outed, noting that his job security, social scene, and parents’ views influenced his decision to avoid the community centre. A more manageable step for some was to enter the Viking Inn, the first pub in Dublin opened specifically as a gay bar by a gay proprietor, according to historian Sam McGrath. Between 1979 and 1987, the Viking stood at 75 Dame Street next to the Olympia Theatre. The building has hosted a public house since the 1920s; today, it’s called Brogan’s. While Brogan’s is no longer a gay bar, much of the décor remains the same—that is, the Viking just looked like your average pub. When two of Karl’s friends brought him to the Viking in the mid-1980s, he hadn’t been aware that they had taken him to a gay venue until he noticed that the various couples at different tables were homosexual.

Despite Karl’s innocence regarding the Viking’s persuasion, another Dubliner, Tony, described the pub as being “notorious” with Dublin suburbanites; they knew that the gays frequented the Viking. Leo J. Mooney’s 1982 Guide to some of Dublin’s Pubs & Restaurants depicted the Viking as “a very fine house of cheer”, encouraging readers to “pop into the Viking for some diversification” after or before seeing a show at the Olympia. Though the guide never explicitly called the pub ‘gay’, the language of “cheer” and “diversification” was likely a sly reveal of the pub’s queer clientele.

The Viking constituted a place of ‘firsts’ for many of Dublin’s gay men coming of age and coming out in the 1980s: the first visit to a gay bar, the first time meeting two men in love, the first time seeing queer affection in public. Ciarán, born and raised in Dublin, recalled taking the bus into town, walking up and down the streets with gay bars, only to take the bus back home without entering.

One night in 1986, he passed by the Viking multiple times, finally turning away onto Parliament Street to head home, when he found an intoxicated man lying in the road. Ciarán helped the man to the sidewalk then walked away, but noticed there was a sticky substance on his hands. His heart pounding, Ciarán finally entered the Viking to use the bathroom—another mental hurdle as he feared what he might find in the unknown of a gay bar’s toilets. Shockingly to him, the inside of the Viking was pretty normal. Ever more shockingly, so were the toilets.

Tony entered the Viking for the first time in 1986 as well. He was with his boyfriend at the time, who had already been “on the scene”. Tony also found the pub to be fairly normal looking, but seeing two older men kissing at the bar was his first real surprise. Despite the fact that Tony had a boyfriend whom he kissed, “It was a real shock to the system to see other people kissing… The act in and of itself was kind of shocking to see two men kissing, but then for them to be doing it in public, oh my god! It was a real… a sudden jolt to the senses.” Similarly, during Ciarán’s first visit to the Viking, he saw a man kiss his male friend on the lips to say goodbye. While the kiss was clearly platonic, that kind of affection between two male friends was unfamiliar to Ciarán, as he noted it as “unreal” and a “moment of oddity”.

Many patrons fondly remember the Viking barman, Frank McCann. A local actor’s memoir includes a story of Frank’s loyal friends and queer community in the pub. Frank moved to Dublin from Cavan, keeping his ‘gay life’ a secret from his family, even when his mother came to visit him at work in the Viking one night. The writer recalled Frank panicking before his mother arrived, telling the men to “butch up” and the “dykes… to look like women, not car mechanics and truckers”. On the night Mrs McCann visited, gay men and lesbians pretended to be boyfriend and girlfriend, as per Frank’s request. Despite being in one of the few places where they were able to be openly queer, camp, and dykey, the patrons all understood Frank’s fear. They straightened in solidarity to protect him, showcasing the power of community found in the Viking.

When the Viking closed in 1987, the same year fire destroyed the Hirschfeld Centre, the pub’s clientele migrated down the street to the Parliament Inn. Today, the building houses the Turk’s Head on the corner of Parliament Street and Essex Street. While a larger gay male clientele frequented the Parliament Inn only after the Viking closed, by the late 1970s, the Parliament had previously hosted a women’s disco and Ireland’s first trans social group, the Friends of Eon.

While some remembered the Parliament Inn as one of the seedier and more hidden spaces, Ciarán and his group of friends affectionately dubbed it ‘the Parlo’, often starting their Friday or Saturday evenings there before heading to the gay nightclubs later in the night. The Parlo offered three floors: the ground floor called The Works, the next called Limelight’s, and Rafters at the top. All three floors catered to slightly different clientele, according to GCN’s eulogy for the bar in 1994. An older crowd favoured one floor; another continued to be frequented by trans people on Thursdays and Sundays.

Pubs such as the Viking and the Parliament Inn were also convenient locations for gay political organisations to target for fundraising and membership. By July 1985, Gay Health Action staged bucket collections in the Viking to crowdsource funds for AIDS leaflets. As central community spaces in which social, political, and health information was disseminated, gay pubs literally preserved gay lives as AIDS spread in Ireland.

These bars, proper pubs, were hugely important as spaces for gay men and women to meet and chat openly. Perhaps the most poignant feeling repeated in many interviews was the ability to simply be oneself without needing to constantly ‘check’ one’s movements or conversation to make sure one’s homosexuality was not on display. Tony described the allure of hanging out in the Viking: “[It] wasn’t just that I could show affection like something as innocent as holding my boyfriend’s hand… but that we could talk without censoring ourselves… We could speak about things—now, it wasn’t ‘let’s overthrow the government’, it was, you know, ‘Oh, did you see… Magnum P.I. or George Michael, isn’t he hot? Or, isn’t he cute? Or, isn’t he sexy?’... It’s a fairly innocuous conversation, but to have that conversation in my neighbourhood bar, where my father might come in with his friends, or my neighbours might come in, that conversation could never be had, except in a very coded way in a non-gay bar. So that was a big revelation. To breathe out.”

While these pubs did not exclusively cater to gay men, many lesbians felt that men dominated the space. A few Dublin dykes took matters into their own hands and started hosting women’s events in a pub on Aungier Street. I hope you’ll look forward to the next instalment of this series, where we’ll talk about lesbian discos and J.J. Smyth’s!