THE SCHULMAN PRINCIPLE

Legendary queer activist, feminist and author Sarah Schulman will be in Dublin this month to speak as part of the Where We Live festival. As Ireland gears up for the referendum on the 8th amendment, she talks to Roísin McVeigh about how successful movements are created and sustained, and the challenges activism must overcome in the age of the hashtag.

“At first America had trouble with people with AIDS,” the announcer says in that falsely conversational tone intended to be reassuring about apocalyptic things. “But then they came around.” I almost crash the car.

This is the story Sarah Schulman tells in her book Gentrification of the Mind, of how she came to co-found ACT UP Oral History Project with Jim Hubbard in 2001. She was in disbelief that after all of the pain, persecution and ignorance that AIDS sufferers had endured, that it was now simply perceived as something that the public “came around” to. She refused to believe that this would be the official history of AIDS, that everyone eventually just came around, because of course, that’s not what happened. That’s not what happened with the civil rights movement, that’s not how marriage equality in Ireland was achieved and that’s not how the impending referendum to repeal the eighth amendment was brought about. In all of these cases, people united in anger over injustice and forced change.

By 2010, Schulman and Hubbard had conducted 128 two-to-four hour interviews with surviving members of ACT UP. Hubbard’s film United in Anger: a History of ACT UP premiered in 2012 at MoMA and has been screened all over the world since. Yet this momentous pursuit is just one part of Schulman’s expansive life’s work. It’s possible that Sarah Schulman is one of the most underrated writers living today. For someone that is relatively unknown in the grand scheme of things, Schulman has had an astonishingly prolific life. She has published eleven novels, six works of non-fiction and written numerous plays. Margaret Atwood recently referred to Schulman’s latest book Conflict Is Not Abuse as “the book of our times.” As an activist, she has been relentless. Most prominent is her aforementioned involvement in the AIDS movement, but she has also campaigned against anti-abortion legislation and is a founding member of Lesbian Avengers. Speaking with her was a lesson in the trajectory of a successful movement, from rallying support in the beginning and staking your claim along the way to the preservation of its legacy in the aftermath.

A SPECTRUM OF ACTIVISM

In Gentrification of the Mind, Schulman discusses meeting young, privileged students eager to participate in some form of activism, but unsure of how to apply themselves. I ask her what she thinks about the current trend of political dressing. How much power is there really in wearing a pussy hat to a march, a black dress to an awards ceremony or a jumper that says ‘REPEAL’? “For some people it’s an entryway into a larger consciousness,” Schulman says. “If it’s a part of a spectrum of responses, then it’s very important. So for some people wearing that jumper is a very important move forward.”

She cautions against pigeonholing and micromanaging people into using the same kinds of words, or pushing people into one strategy, a style of activism that she sees as a trend today. This will only lead to the cannibalisation of a movement. The clumsiness of the burgeoning #MeToo movement with its one-size-fits-all hashtag comes to mind. Lack of clarity has led to innumerable debates and gossip-mongering across the internet, distracting from the bigger issue at hand, the actual solution to be found in investigating the social structures in place that accommodated these assaults in the first place.

Schulman expands on her point by referring to the history of ACT UP.

“The movements that can accommodate all kinds of responses are the movements that are most likely

to succeed.

The AIDS movement was extremely broad, which allowed people to respond from ‘where they were’, whether that was as a victim, a friend, a family member, or a member of society that refused to tolerate the injustice that they were witnessing.

This breadth, says Schulman, was the key to the movement’s success. “If movements try to force people into taking stances or responding in one certain way, they will fail,” she says. “The movements that can accommodate all kinds of responses are the movements that are most likely to succeed.”

LEARNING FROM THE PAST

According to Schulman if you look at the successful movements of the past, you will find that many of them have similar structures. It was while reading Martin Luther King’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’, that she realised the strategy he had outlined for the civil rights movement closely resembled that of ACT UP. First, Schulman implores, you must become an expert on your issue. The second step is to construct a solution.

“Instead of being tantalised by asking the powers that be to solve the problem, you solve the problem,” she says. “In other words, don’t wait for the change to happen, because change doesn’t just come around. Then you present your solution to those in power. If they refuse, the next step is ‘nonviolent civil disobedience training’ or as Dr. King calls it ‘self-purification’.”

“In other words, don’t wait for the change to happen, because change doesn’t just come around.

What is that exactly? “It’s when you prepare to take direct action in order to communicate to the media, to the larger community, about the merits of your solution that you have designed.” And how do you do that? Schulman specifies that creativity here is key. It is essential to capture the attention of the media.

BEYOND THE HASHTAG

This is where activism goes beyond a hashtag or a slogan t-shirt. Schulman refers to the Greensboros sit-ins as “probably the most visionary” protest of this kind. This was a direct action that occurred in the 1960s in North Carolina, where African-American students staged a sit-in at segregated lunch counters in North Carolina. They were spat on, targeted with racist insults and eventually arrested, but they refused to respond at any point with violence.

Heavy media coverage of the sit-in sparked a sit-in movement that spread throughout college towns across the South and into the North. The initiators, or The Greensboro Four as they became known, were inspired by the non-violent protest actions of Mohandas Gandhi. Violent action doesn’t portray any viable kind of solution. On the other hand this image, although it was only carried out by a handful of people, showed the world, through the amplification of the media, what they wanted to achieve. “They weren’t saying please integrate this counter, they integrated the counter, even if just for a minute, that is the most successful kind of action,” says Schulman. “The kind of action that shows the world what you actually are fighting for.”

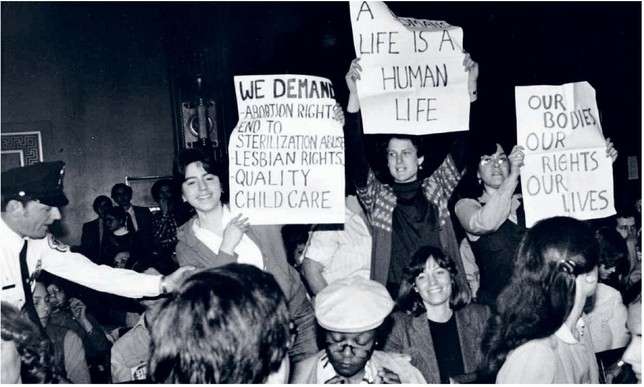

Schulman points to another direct action protest, one which she was involved in. It was 1982 and Ronald Reagan had just been elected president. An anti-abortion bill was being put to congress live on TV. Schulman and five other women interrupted the congressional hearing on live television with signs that they had smuggled into the proceedings. When a witness testifying said “a foetus is an astronaut in the uterine spaceship” this was a straw that broke the camel’s back. The women stood on their chairs and held up their signs and said “a woman’s life is a human’s life.” The arresting officer testified that Schulman had said: “Ladies should be able to choose.” In an interview with Pen America, Schulman was quoted as saying “I think that the idea of a woman’s life being a human life was too complex.”

DAY OF DESPERATION

Schulman again returns to ACT UP. This time it’s to tell me about the ‘Day of Desperation’ protest in 1991, when activists disrupted the CBS Evening News live broadcast shouting “Fight AIDS, Not Arabs!” in response to President George H.W Bush’s claim that there was no money for AIDS funding, while racking up a billion dollar expenditure on the Gulf War. This spawned actions across the five boroughs of New York, culminating in a milestone event in Grand Central Station where a banner reading “Money for AIDS Not War” was raised with helium balloons to the ceiling. “These types of direct actions which show the world, what our business is, is how we convey that we have these solutions in place,” Schulman says “if it’s successful you force the public opinion. You can change the paradigm.”

What each of these movements exposes time and time again is a clear power imbalance, not one that revolves exclusively around sexuality, colour or gender, but often around class. What Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Repeal the Eighth and the many other contemporary movements happening throughout the world today have shown us is that although our inequalities have evolved, they still run deep. To go back to the dilemma of Schulman’s ambitious but privileged and slightly lost students: with so much to fight for, where does one start, where does one focus one’s energies?

“We need to protect the most vulnerable person,” she says. “So the person who is being scapegoated, the person whose being blamed, the person who is being shunned. That’s the person we should be reaching out to. Right now the main social objects of hate are immigrants, undocumented immigrants, muslims, black people, trans people, poor people. People who are vulnerable to state violence. They are the people we should be reaching out to and standing with. And in our immediate lives, people in our circles who are being blamed or scapegoated. We are in an ever expanding concept of society, not a retracted one.”

Sarah Schulman will give the keynote address for THISISPOPBABY’S ‘Where We Live’ Townhall sessions as part of the St Patrick’s Festival on March 10 at 2.30pm.