History - Decriminalisation - Policy

Coverage of Decriminalisation

June 2023 marks the 30th anniversary of what is commonly referred to as ‘Decriminalisation’; essentially, the passing of the Sexual Offences Bill 1993. Han Tiernan looks back at the progression of the movement and how it was covered in the pages of GCN -Ireland’s national queer press.

The Sexual Offences Bill decriminalised acts of ‘buggery’ and ‘gross indecency’ between consenting males over the age of 17. Suffice it to say, a bill of this magnitude was not passed lightly or overnight; in reality, it was a hard-won fight that had begun 16 years earlier when Senator David Norris first brought a case to the High Court against the Attorney General.

Norris’s case failed in the High Court and was later rejected in the Supreme Court, prompting him to challenge the Irish rulings in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). He argued that the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, which criminalised “buggery”, and the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which referred to “gross indecency” – covering all other sexual contacts between men, otherwise known as “the laying on of hands” – were in breach of his right to privacy under the European Convention on Human Rights.

In 1988, following a five-year review, the European Court finally found in favour of Norris, recognising that the existing legislation contravened article eight of the Convention. Accordingly, as a signatory to the ECHR, the Irish Government was obliged to amend the archaic Victorian Laws.

But the success of Norris’s case was just the start of a further five-year battle to get the Government to overturn the legislation – one which would involve intense lobbying by the LGBTQ+ community and other civil rights organisations.

While the ruling and advances in the subsequent five years garnered widespread media interest, a newly released queer magazine paid particularly close attention to the proceedings.

Launched in February 1988, GCN was the brainchild of Tonie Walsh and Catherine Glendon, published under the National Gay Federation (NGF, later NXF). From the first issue, GCN pledged its allegiance to the cause, dedicating an entire page of its eight-page issue to outlining the precarity of the laws and their implications on gay men. In the article aptly titled ‘Bugger Off’, barrister Jim Treanor highlighted the laws’ impact on wider society in informing negative attitudes towards homosexuals. He also suggested actions the community could undertake “to do their bit for this worthy cause”. These ranged from joining a political party to writing letters to newspapers.

The front page of Issue 8 (Sept 1988) contained a report by Walsh about a Law Reform Seminar held on September 17. Along with Kieran Rose informing the attendees of the trade unions’ actions on employment equality, Tom Cooney, Chairperson of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL), discussed the Working Party that had been established within the organisation to undertake the task of producing a policy document on lesbian and gay rights.

On page three of the same issue, in a short article titled ‘Norris Judgement Soon’, readers were reminded that a favourable outcome was predicted due to a similar action taken by Jeff Dudgeon against the UK Government in 1982, leading to a change in the laws in Northern Ireland.

Although the magazine was intended to be a monthly publication, the first year’s output was erratic due to financial instability and staffing problems resulting from migration. As a result, there was a four-month gap between Issues 9 and 10, meaning the magazine missed out on reporting on the October 26 verdict from Strasbourg on Norris’ case.

Coverage of the campaign resumed in Issue 12 (October 1989) with a positive news report titled ‘No To Anti-Gay Laws’. It referred to a study released by the Law Reform Commission. The research included a comprehensive investigation into the law affecting relationships where it concluded that the existing anti-gay legislation should be amended. In a further endorsement, it found no reason to set a higher age of consent for “homosexual consensual conduct” compared to heterosexual activity.

The words, ‘Our Demands’, were emblazoned across the front of Issue 13. The article was penned by Rose, now the co-chair of the newly formed Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (GLEN). It was “set up to provide leadership and coordination in this Law Reform campaign”. It comprised various groups, including the Cork Gay Collective, Gay Switchboard Dublin, Gay Health Action and the NGF.

As well as highlighting the government’s obligation to uphold the European ruling, Rose outlined GLEN’s demands for the introduction of anti-discrimination legislation concerning: housing and employment, an end to discrimination of lesbian and gay men regarding custody, succession and pension rights, and the introduction of non-judgemental sex education in schools.

The following two years saw intense pressure on the government and small wins. In October 1989, the Dáil passed the first legislation granting rights to homosexuals through the Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Bill. In Issue 17 (April 1990), Margaret McWilliam reported on the launch of the ICCL report Equality Now for Lesbians and Gay Men. At the event, Cooney declared, “It is important that everyone shame the Government into responding; it is the most fundamental human rights challenge facing the Government today...it is fair to say that we have the worst record in legal discrimination against lesbians and gay men [in Europe]”.

May saw Family Solidarity, one of the most vigorous opponents to amending the law, publish The Homosexual Challenge: Analysis and Response booklet. Whilst Jonathan Wallace described it as “a clever piece of work” in his report, he and Don Donnelly, co-chair of GLEN, felt it was necessary reading for all involved in the campaign for law reform – “Know your enemy!”

Two years on from the Strasbourg ruling, in Issue 24 (November 1990), Frank Thackaberry reported that Norris had instructed his solicitors to re-submit his case to the ECHR seeking punitive damages due to “the long delay in bringing Ireland’s law into line with the European Convention on Human Rights.” The following month, GCN reported that Ireland was being called to account for its inaction over the ruling.

1991 started positively when the February issue of GCN reported that the then Minister for Justice, Ray Burke, confirmed that he would present the new legislation to the Senate by the end of the year. Furthermore, a cabinet reshuffle in March suggested that Minister Burke’s workload had been lightened to allow him more time to concentrate on law reform. However, by October, a spokesperson for his Department confirmed that fears of the legislation being further delayed were likely.

1991 also saw a troubling ruling on a rape case. In Issue 28 (March), the ‘Sex Crimes’ article reported that a man had been sentenced to two years imprisonment under the 1861 Act. Although the man had been charged with raping and indecently assaulting his former girlfriend, the judge and jury decided the charges had not been ‘proven beyond reasonable doubt’. However, since the man had admitted to having anal sex with the woman – asserting that it was consensual and the woman had introduced him to it – the court convicted him of ‘buggery’.

Ironically, the government had claimed the 1861 law was never enforced during the Strasbourg hearing the previous year. Moreover, the solicitor for the convicted man said that they would appeal the sentence to the Court of Criminal Appeal and the ECHR, citing Norris’s case as precedent. Although various politicians and community leaders had lent their support to the campaign, 1992 brought little advancement. With Albert Reynolds becoming Taoiseach, a new ministerial cabinet was appointed, creating confusion over when the reform might be tabled. By November, a general election had been called, resulting in a Fianna Fail/ Labour coalition forming in January 1993.

Immediately the new government proved more progressive, appointing a dedicated ministerial post with special responsibility for equality. The decriminalisation of homosexuality was also included in the programme for government, with Máire Geoghegan-Quinn being appointed Minister for Justice. By February, Minister of State for Labour Affairs Mary O’Rourke introduced sexual orientation into the Unfair Dismissals Act.

The front page of Issue 51 (May 1993) posed the question, ‘Legal at Last?’. The article broke the news that the Department of Justice had begun talks on law reform, citing a leaked draft memorandum as its source. Essentially, the document suggested that two options were being presented to the government for consideration. The first option would bring Irish law in line with Britain, meaning the existing legislation would be amended to permit an age of consent over 21 and only in private. The second option would repeal the 1861 Act and parts of the 1885 Act and then introduce new legislation protecting young persons.

By May 18, the Government Information Service released a statement saying, “The Minister for Justice, Mrs Maire Geoghegan-Quinn TD, today announced that she had secured government approval for her legislative proposals in response to the Judgement of the European Court of Human Rights in the Norris case.”

It continued, “On the Minister’s recommendation, the Government agreed to repeal the existing law on homosexual acts and to enact new provisions prohibiting such acts with persons under 17”.

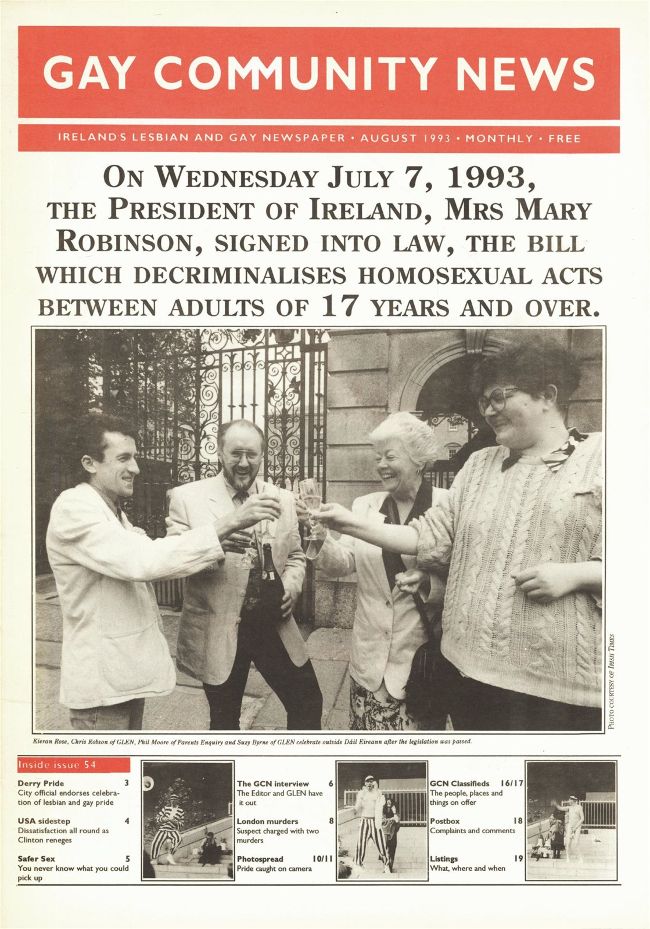

The Dáil eventually passed all stages of the Sexual Offences Bill 1993 on June 24. It was passed by the Seanad on June 30 and was signed into law by President Mary Robinson – who had also been legal counsel on Norris’ case – on July 7, 1993.

The iconic photo of four people toasting glasses of champagne outside the Dáil on the front page of Issue 54 (August 1993) was the first full-page photo GCN had ever printed. To this day, it is a most fitting tribute to the incredible campaign that Norris and the community had fought so incredibly to achieve “decriminalisation”.