Conversations In Monochrome

From the embrace that empowered the marriage equality referendum in Ireland to the kiss that made Northern Ireland question itself, Joe Caslin is renowned for invigorating social commentary and astounding art works. Speaking to Oisin Kenny, he highlights the power of empathy and conversation within times of social change. All images provided by Joe.

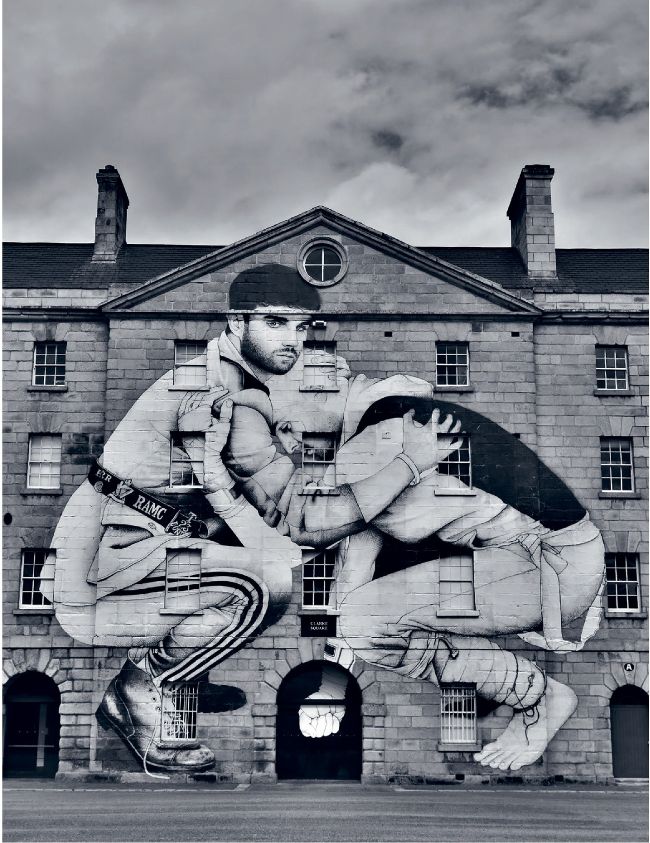

roe Caslin’s monochromatic goliaths have stood tall and proud on the walls of urban spaces. The towering size of the subjects convey the thematic weight of the social issues they grapple with; from mental health to addiction to LGBT+ rights., each one silently sounding out a call for action, bringing passersby on the street to a halt.

“I’m lucky that one of the best things that was given to me at home was a sense of empathy,” Caslin said. This sense of empathy resonates throughout his monochromatic style. Without text to guide the viewer, they must instead read the body language of the subjects, searching deep within the art to find their own meaning, their own truth.

On the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, Caslin travelled to Manhattan as part of the World Mural Project to create a piece depicting two same-sex lovers, one free and one restrained. His piece contained subtle hints at “a very Irish conversation” around the contrasting realities of LGBT+ rights in Ireland and Northern Ireland. He said the piece was created “to showcase where Ireland has come over the course of the last four years since the vote and how ridiculous things are up the North, how our family, our brothers and sisters in the North don’t have the same rights.” World Mural Project was set up “to create something that would express our defiance, our fears, our gratitude and our pride,” states the Project’s homepage. The initiative came about through New York City Pride working in collaboration with LISA Project NYC, HSBC and Macy’s.

In relation to Caslin’s own contribution, he said, “It was important that the piece spoke about how the situation is on the island of Ireland but also to remember Stonewall after 50 years. It was important that sense of rebellion, or that sense of revolt, is still active in the community.”

Each of Caslin’s murals are born within the fight for social equality rather than from the perspective of commemoration. This is embodied in the Manhattan mural which not only honours the history of Stonewall but situates the two lovers within current social struggles through subtle references, such as a crucifix earring and a badge on one of their sleeves. He said that his strength lies in the moments when “I’m trying to advocate for something that is an injustice until it becomes something that is answered. [...] I think that my best weapon is in the fight up to that point.”

In 2016, Caslin designed a mural of two women on the verge of kissing as both a celebration of Belfast Pride and as a means of drawing attention to restrictive same-sex marriage rights in the North. There was a mix of both positive and negative reactions to the artwork from people within and outside the Northern community. “When the drawing goes up on the wall, it is there to provoke and it is there to start a conversation, get a community to hopefully look at a topic. Whether they engage with the conversation out loud or internally, the conversation has been touched on.”

The Belfast mural followed a year after Caslin’s legendary piece titled ‘The Claddagh Embrace’ on George’s Street. As the fight for the marriage equality referendum reached its peak in 2015, two gigantic men embracing on the side of Rick’s Burgers became a powerful symbol of the pro-marriage equality side. Caslin said, “In big conversations, the role of art is sometimes forgotten. Culturally, it is really important what we produce visually in the country.”

“A community was mobilised into action to not only protect the mural but also what it stood for”

With the emergence of ‘The Claddagh Embrace’, a debate ensued over whether the artwork required planning permission and as such should it be removed. While Dublin City Council debated amongst themselves over what to do about the piece, with many Councillors voicing their opposition to it, numerous petitions started appearing online. One of the petitions said, “We are asking that Dublin City Council do NOT buckle to the pressure, and allow the mural to stand high and proud on South Great George’s Street, Dublin 2.”

Through ‘The Claddagh Embrace’, a community was mobilised into action to not only protect the mural but also what it stood for. “It was like there [were] people going into battle for it because it meant something. It was a visual representation of same-sex love and we didn’t have that,” Caslin said. Though he knew there was a power in the drawing, he did not expect the extent to which people took ownership of it and fought so strongly for it.

The mural on George’s Street is a testament to Caslin’s ability in “looking and finding buildings and shapes that were in the urban environment, then trying to fill them so that the building and the drawing were in conversation with each other, or the space was in conversation with the drawing.” However, working towards the goal of harmonising the urban space and socially charged art was a “slow movement”.

Caslin originally designed illustrations for books and magazines but the work did not engage with the audience as he had hoped. Through experimenting with different styles, he found street art as the best way for him to connect with people and begin conversations around heavier social issues. “With the rise of art within the urban environment, it just made the most obvious sense for me to create conversations using that medium,” he said.

In 2016, Caslin worked alongside Niall Breslin to create a massive mural in Waterford city of a man being pulled in three directions to continue the conversation around mental health. The mural, produced through a collaboration with Waterford Walls, A Lust For Life and Pieta House, has served as a guardian. Horticulture WIT wrote on Twitter, “Whenever we see Joe Caslin’s Waterford Walls piece we’re reminded to look after each other.”

“It’s looked over and minded that city for the last three and a half years. [It’s] really important that stuff like that exists,” Caslin said.

“I’ll only engage with subject matter if I have a personal experience of it,” Caslin said. After tragically losing five students, he began to produce murals examining mental health and the stigma around it. His first major project, ‘Our Nation’s Sons’, was in response to the loss of his students - a project spanning across Ireland depicting young males wearing hoodies as a confrontation of the country’s apathy towards them.

Caslin’s students have provided a constant source of inspiration and motivation for his murals. In the aftermath of a Cork rape case where the defending barrister held up a woman’s underwear as a sign of consent, a group of his students were outraged. He said, “They came up to me and they go ‘well, you have a platform and you have a voice so why don’t you’, and these were the words they used, ‘just fucking make a piece on it.’”

Taking their words to heart, Caslin established two murals in Waterford and Dublin as a means to highlight the importance of consent. One piece depicts a woman writing the words “I said no” while gazing out in defiance. “It was through [those] kids saying to me - ‘well, this is us, we are young women, this is our country, and this is what’s happened to us.’” In only a short space of time, Ireland has undergone monumental growth as a result of the marriage equality referendum and the repeal of the Eighth Amendment.

With same-sex marriage and bodily autonomy rights on the horizon for Northern Ireland, communities are pushing for change, speaking up against injustice, and are willing to engage in, often times, tough conversations. As Caslin said, “With the two referendums, it has inspired a whole generation of community and empathy, and a kindness basically, and that’s lovely and it’s nice to be part of that.”