Wilde Thing

Whether you recognise him for his iconic roles in films like Another Country or My Best Friend’s Wedding, his controversial statements about the movie industry, or his warts ‘n’ all autobiographies - Rupert Everett is a proper gay icon. Now he’s delving into filmmaking with a movie about the last few years of Oscar Wilde’s life. Aoife O’Connor sits down with the man to chat about what it means to embrace being an older, openly gay actor, and entering a new phase of his career.

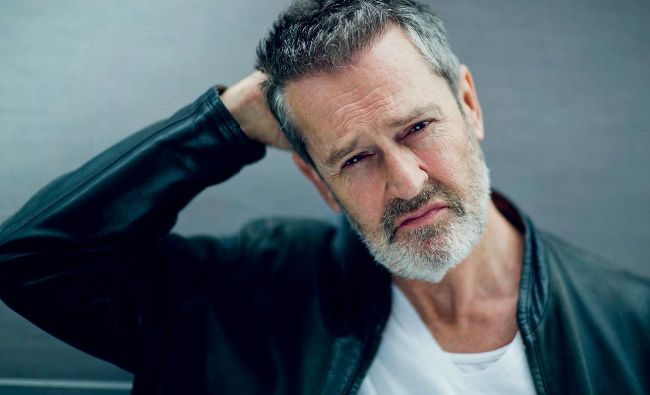

We are sitting at a table in the Merrion hotel. It’s 10am, and Rupert Everett is tucking into some tea and toast. It’s only now that we’re face-to-face I realise the severity of the physical transformation he took on to play Oscar Wilde in his latest venture The Happy Prince. It marks Everett’s first foray into producing his own film, and centres around Wilde’s final years in France following the two years he spent in prison after being convicted of gross indecency. Everett hasn’t done any time for being openly gay in Hollywood, but it certainly hasn’t been easy. He’s never been afraid to speak his mind, calling out the movie industry for being inherently homophobic, and expressing regret over coming-out so early in his career. His controversial opinions have landed him in hot water over the years, and his several autobiographies are littered with off-hand insults about past co-stars (he’s called Madonna the antichrist). That doesn’t take away from a career littered with iconic roles, like the dashing George in My Best Friend’s Wedding or Prince Charming in Shrek. He may have worked himself to the bone to get The Happy Prince off the ground, but Everett still manages to ooze smooth charm over breakfast. He’s as profoundly well-spoken as I had hoped he’d be, and has a passion for cinema and filmmaking that has resulted in a Wildean triumph.

“I adore Oscar for those warts-and-all qualities, for the flaws, because I can see myself falling into the same traps.

‘The Happy Prince’ has been a long-time in the making. What was this journey like for you as a first time filmmaker?

Well, it started about 11 years ago. A lot of independent cinema takes a long time to get together and find the money for, but it was a long, long journey. At one point, I had an Irish producer who said: ‘You know, Rupert, there are some films that just don’t want to be made, and this is one.’ In a way he was right because everything about it was kind of lopsided. It had a difficult birth, but here we are.

The film fills in a chapter of the Oscar Wilde story that we’ve never seen on screen before – his exile in Paris after serving hard labour. When you began the process of creating your own project, was this always the story you wanted to tell?

I suppose that if I was ever going to make one film in my life, I would like it to be this one. It has something for every homosexual working in the system, against the system or brushing against the system. You can’t fail to think of Wilde as a patron saint or a kind of Christ figure.

There’s a lot of love for Wilde in this fi lm, but also a lot of honesty about his character. You’re portraying him at absolute rock-bottom.

I’ve been very touched by the story of Oscar in exile, the punishment after the punishment. Liberty was another punishment for Oscar, a long drawn-out crucifi xion. Personally I feel that the story should be told because all gay people have a moment of, not crucifi xion, but a brush up against the structure of the majority, and obviously, I have too. It’s been a part of my life, being gay in an agressively hetrosexual boys-club world, and so this is the story for me.

I don’t think Oscar was a saint. Sometimes people sanitise the big stars too much. For me, those people aren’t like that. They’re normally human beings, and Wilde is really, really human. The reason why he’s such a Christ fi gure for me is because he has his genius, which is his godliness, and then he has humanity, but the humanity that we all have – snobbery, greed, laziness, ego and vanity – all these things undid him completely.

Most of us have all those qualities but manage to keep going somehow, and it’s for his humanity that I adore him really, because it was just a catastrophe, what he did. I adore him for those warts-and-all qualities, for the fl aws, because I can see myself falling into the same traps.

You’ve had a career full of iconic roles, for one generation it’s ‘Another Country’ and ‘My Best Friend’s Wedding’, and for another it’s ‘Shrek’ and ‘St.Trinians’. Is this the next chapter for you?

I’d love to start a new chapter. I feel that it’s opened a new door into my dream world, but on the other hand, I am 60 and this is a very young business. You need nerves of steel and my nerves are a little bit like an old bicycle with no brake pads, so I have to wait and see. I’ve got tons of ideas that I want to do.

Like all people getting older in a business, you want to keep engaged if you can and keep part of it. It’s very diffi cult I suppose in the new virtual world. It’s so alien to me, but I feel in a way that’s a good thing. I feel someone should be, not defending, but reminding people that there was a world before six months ago.

The thing about the new virtual world is that we’ve given up completely on history in everything. I think that history is the great tranquiliser in a way, because we live to a kind of recipe for catastrophe all the time. Everything’s so fereverish in what we need to achieve now, and I think that’s because we only have a six-month perspective. For example, if you look at being a gay person today and then at Oscar, there’s this huge leap that’s been taken for me to be sitting here so at ease now.

Oscar’s story would probably be about halfway across the spectrum of the global gay experience. There’s a huge journey that hasn’t been taken in the world in places like Russia, Jamaica, and Uganda. I think that knowing this history and being familiar with it is incredibly good for us because it gives us perspective and makes us – makes me – feel less neurotic about where I am now.

So would you say that Oscar’s life still has a lot of relevance to LGBT+ people in the 21st century?

Being gay is still a life and death thing in many parts of the world. It’s really dangerous, so I think it’s the extraordinary thing about Wilde – he really seems to cross the ages.

One of the things that I personally love about his deathbed is that living through AIDS in the ’80s, when everybody’s friends started getting ill in a really graphic and horrifi c way – a lot of us ended up in long drawn-out deathbed scenarios with groups of friends, with one person getting iller and iller. Oscar’s deathbed has a touch of that in it somehow, before it all happened. So he remains relevant to everything that we’re still going through, he somehow still speaks to us, or to me anyway.

You’ve never been shy about discussing your sexuality, and have played a number of gay men on screen. Now with this fi lm, we get to see you in the older gay man role. Do you feel that playing into your sexuality is something you’ve embraced or is it something you’ve felt boxed into? I’ve completely embraced it, I love playing gay roles. I suppose I would like there to be more interplay between the one direction thing of straight guys playing gay roles and gay guys playing straight roles. It’s a shame that it doesn’t work both ways particularly.

I don’t think I’d have felt so happy if I hadn’t managed to pull off this fi lm. In the last three years when it looked like I wasn’t going to make this fi lm, I really thought – well actually I knew – I would cease to exist. I feel at least, even if I stop now, that I’ve made a statement I feel very happy with. This fi lm is not about me, but it’s got all of me – everything I have – in it.

‘The Happy Prince’ is in cinemas on June 22