When lauded Irish writer PP Hartnett told us he doesn’t want to be “the usual safe fag who isn’t going to gamble” in order to get his books on the shelves, we decided we wanted to hear more. Celebrated for his 1996 queer novel, Call Me, he’s since rejected the mainstream to create his own publishing company, collaborated with gay serial killer Dennis Nilsen, and formed a band called Child Rape Photos. As his latest collection of poetry, or what he calls “thought grenades”, is published, he tells Gavin Whelan it’s all in the service of wanting to tell the truth about the ip side.

Intelligence isn’t always reflected in numbers,” says PP Hartnett. He’s talking about social networking, or “Facebore,” as he calls it, responding to a question I’ve put to him about whether there’s such a thing as a subculture anymore.

Which is the real self? Is it the nine-to-five person in the suit, or is it the person in a jockstrap, boots and a balaclava, posting his pictures on recon.com? How many selves do we have in our closets?

“The people who are innovators and originators, they don’t tend to twitter, which is a desperate form of attention seeking. It’s such a load of tedious bollocks. The level of the functioning of communication is skimmed milk rather than organic whole.”

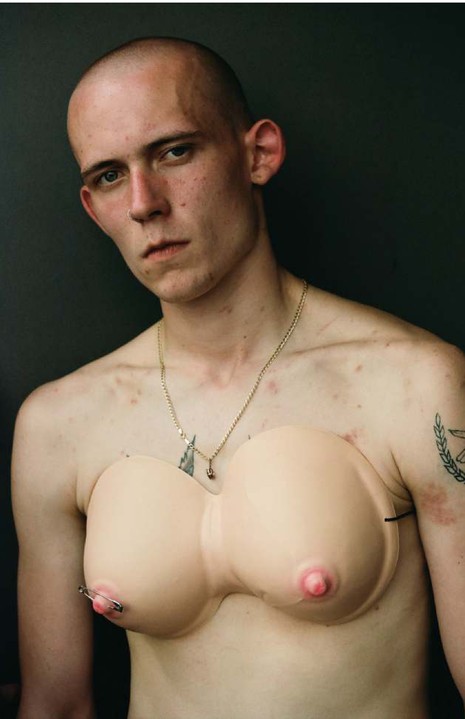

Leeds Skinhead, Rebellion Punk Festival, Blackpool, 2016

Such juicy soundbytes are par for the course with 59 year-old Hartnett, who has produced three novels, one short story collection, a photography book and two books of poetry, since his debut, Call Me garnered international acclaim 20 years ago. He tends to talk in statements, announcing opinions and telling tales, so while on one level he’s got plenty to say, on the other it’s often hard to get a firm grip on the content of his conversation.

The son of rural Irish parents who emigrated in the 1950s, he grew up in the London suburb of Ealing, “weighed down with shamrock”. He’s since given up his British passport in favour of his Irish one.

There they are in the sling, with nipple clamps and a jockstrap on, and a tub of Crisco to one side, but it’s what they write that I’m drawn to.

“My genetics are so entrenched and part of me, it’s kind of beyond my control,” he says. “Growing up, there was almost a schizophrenic quality to it. My mother would talk to us in Irish at home. My father would bring fellows home of an evening, they’d be sitting in a circle in the kitchen and there would be all kinds of tales and songs. When I’d go to the homes of other kids from school, they’d all seem so lame and tame.”

His Irish emigrant family, of course, had a resolute devotion to the Catholic Church, and Hartnett was sent to an all-boys Benedictine private school, the name of which has since become notorious in the UK, for all the wrong reasons.

“My parents lived for the church,” he says. “They held up the priests as idols in a way, so you didn’t say that priest tried to kiss me, that priest touched me, that priest’s hands were all over me. You didn’t say anything.”

His experiences at St Benedict’s, which was condemned in a 2011 public enquiry for a “lengthy and cumulative failure” to protect pupils in its care from child abuse, became the subject of Hartnett’s first novel, Butterflies and Moths, Murdered and Mounted, which he wrote at the tender age of ten.

“I was in effect educated within a paedophile ring,” he says. “Weird was normal, as it is in any dysfunctional set-up. When I was ten, my best friend died suddenly in the night and I insisted that I wasn’t going to go to school for a few weeks. In my time away from it, I blistered the index finger of my right hand bashing away on a Remington typewriter, as I typed over and over this little story about a boy seeking revenge on an abusive school, where there were sexually predatory Benedictine monks. I couldn’t tell my parents what school was like. I could only write it.”

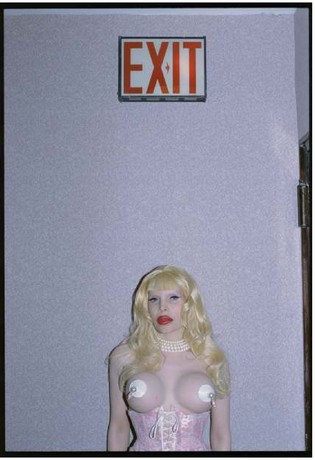

Amanda Lepore, Hotel 17, NYC, 2002

ZIGGY STARDUST BOY

While the dark subject matter of that first novel has underpinned most of his writing since, the precociousness Hartnett showed as a child writer translated into a penchant for photography as he came of age, finding himself on London’s punk scene in the late 1970s.

“There I was, going out to pubs and clubs with the boy from the next road, who was later renamed as Sid Vicious,” he says. “He was forever coming around my house to borrow my Iggy Pop records. I knew him as a Ziggy Stardust boy, a Bowie fan more than anyone else, with kohl around his eyes and t-shirts from Sex in the King’s Road. Then he went skinhead. I went to a Sex Pistols gig, just because I was attracted by the name, and there he was on stage, pogoing away.

“So many of us on the fringes of punk were gay. When the punk thing fizzled, which it did quickly once heroin came on the scene, we went back to our Bowie roots, but because we’d been through that bizarre, really energised moment of punk, we’d learned so much and it had changed us. What we all wanted was to do our own thing. We didn’t want to be spectators, we wanted to be originators.”

Hartnett’s photography at the time explored the heady moment of intersection between youth and gay culture that has now come to symbolise the late ’ 70s and early ’ 80s pop world, and he was surrounded by artists and musicians like Leigh Bowery, Trojan, George O’Dowd [Boy George], and Steven Harrington [Steve Strange]. In the years since then he’s continued to take photographs of kids on the queer cultural intersection, while his writing, from the publication of Call Me, a graphic exploration of the subversive queer sexual underground, has honed in further and further on what Hartnett calls “the flip side of the gay community”.

“I’m interested in the hard drive of the contemporary gay scene,” he says. “There is a very healthy, constructive element within the gay community, but there’s also the flip side, which is dark, exploitative and manipulative. When I pick up a gay magazine, I don’t want to see buff models, and I don’t want to see people talking generic rubbish. It’s still difficult being queer, it’s still full of challenges, and within queerdom there are all kinds of levels of functioning.”

With Call Me, and subsequent novels I Want To Fuck You, Sixteen and Rock ‘N’ Roll Suicide, and with his short stories and poetry, Hartnett has consistently found his route to the flip side by reading between the lines and gauging the underlying sexual atmosphere. It’s something he relates back to his school experiences.

“I’ve always had an interest in sexual compulsion, sexual fixation and addiction, and I think so much has to be blamed on those Benedictines,” he says. “I’d rather spend an hour zigzagging through the profiles on Recon.com or Trakkies.com or Fitlads.net than read the latest book by Alan Hollinghurst or Patrick Gale. There are pictures of guys in slings, with the nipple clamps on and a jockstrap, and a tub of Crisco to one side, but it’s what they write that I’m drawn to. I’m always seeking a kind of reality within those profiles.

“Which is the real self? Is it the nine-to-five person in the suit, or is it the person in a jockstrap, boots and a balaclava, posting his pictures on recon.com? How many selves do we have in our closets?”

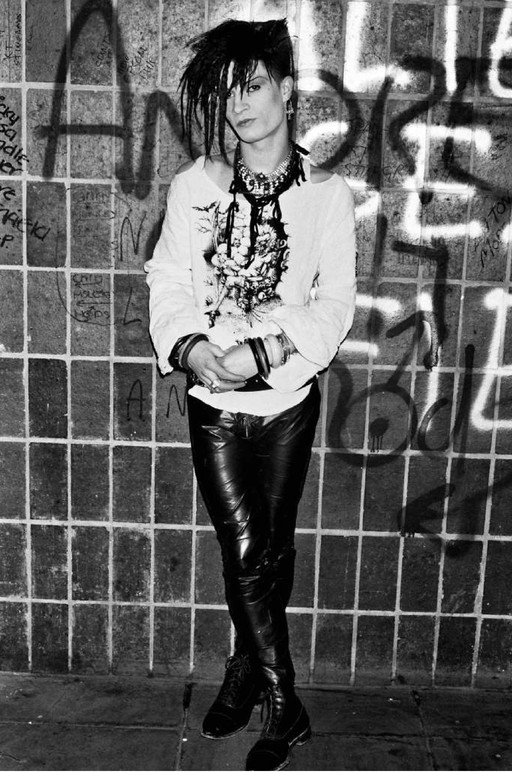

Goth at The Batcave, London, 1984

“ When I pick up a gay magazine, I don’t want to see buf models, and I don’t want to see people talking generic rubbish.

KILLER AESTHETIC

This interest in the multiple secret selves led Hartnett into a lengthy correspondence with the gay serial killer and necrophiliac, Dennis Nilsen, a Job Centre clerk who murdered at least 12 young men in London between 1978 and 1983, and ended up illustrating the cover of one of Hartnett’s books.

“I first contacted him because I wanted to explore his aesthetic, which might be an unusual word to use for exploring the mindset of a serial killer,” Hartnett says. “I wasn’t seeking a friend, or a lover. I didn’t want to enter a cosy relationship or anything like that. Sometimes people refer to themselves as magpies when researching; I’m more like a hawk. I knew exactly what I was doing, what I was getting involved in, so there was this kind of clinical, manipulative, exploitative side of myself within that situation. I was digging.

“The last thing I expected was to correspond with the man for ten years. I got to understand his mindset so much, that it was almost contagious. He wanted me to edit his biography, which I certainly looked at, and engaged myself with, but in terms of responsibility, I had to ask myself a question: could this manuscript, if published, act as a trigger on somebody who is already slightly on the path of being a sexual predator and maybe having a slightly sadistic edge? I felt it was something not to be published, so I raised concerns and that ended all contact.”

Sexual predators make up the queer core of Hartnett’s latest poetry collection, three men, in tears, which has as its subject three predators, each of whom represents themselves to their prey in different ways. Hartnett writes his poetry with a word collage method, much like the approach David Bowie employed for his lyrics, and when he talks about the work, he scatters across subjects and titles, giving hints of what’s behind them rather than painting a whole picture.

PP Hartnett: “We live in an age where so much is deleted.”

“They end up in court,” he says of the predators in the book. “They all get caught. They’re very much rooted in today’s world, online, on scene and away from the scene. ‘Tumblr and Instagram Shit’ is about a guy who has been exposed to pornography for so long, it no longer hits the mark. He’s got to create his own porn; he’s got to be the star in his own little film world in his head. And then ‘Neoprene Cocksucker Hood’ is about that whole thing of wearing a mask, and is this the real person, or is he just acting out a role?

“The final piece is called ‘Resize, Rotate and Pixilate’. We’re not sure if it’s some sort of computer game a guy on chems is playing, or if he is actually there and he’s so used to living life through a screen that he’s split from real life.”

STUPID FUCK SLUT

This poem is immersed in another theme that’s has become key to Hartnett’s work, the rise of the Internet and its effect on our sexual selves.

“I find there’s a big disassociation because of online life,” he says. “Porn is often used now to shift mood, not just to direct hard-tissue. Porn runs from the screen like water from a tap, and we don’t know our hearts and minds are genetically responding. It’s just there with us, in the living room, in the bedroom, wherever we are, whatever we’re doing.

“I’m in contact at the moment with online somebody who is professing at the moment to be an 18 year-old ‘cum dump’. I don’t know whether he’s really 18, or he’s 58, but this guy is promoting himself as a ‘stupid fuck slut’. He sends me a message every day, calling me Daddy. When I see people promoting themselves as ‘cum dump fucksluts’, it’s incredibly worrying. I don’t find it funny and I have to explore it. I have to work with it and see the logic within it, because often there is a logic – a very precise logic.”

In a climate where those who say the unsayable are punished by the online mob, it’s not surprising that publishers have shied away from the increasingly sexually subversive subject matter of Hartnett’s work. In 2015, he created a multiple platform work called child rape photos, which included a book and a play about fictional television documentary that featured four ‘survivors’ of many years of systematic abuse within a fictional London faith school, and a band mirroring the punk band in the work, also called child rape photos. However the book’s online distributor lulu.com was bombarded with complaints, while the band’s music was removed by the distributor, Tunecore. As a result, Hartnett changed the title and the name of his punk band to deletion.

“We live in an age where so much is deleted,” he says. “For instance, the trustees of a Catholic school can actually just destroy files and things go missing.”

three men, in tears, like Hartnett’s previous poetry collection, date of birth, time of death, is published by his own company, Autopsy, which allows him to do exactly what he wants to do, without censorship, while giving him a platform for previous work he’s got the rights back for. “I enjoyed mainstream publishing,” he says, “but now I’m putting out work that I want to put out.

“I’m deadly serious about what I do, and that’s because I just want to tell the truth. I don’t want to write a hilarious romp that’s aimed at translation rights; I’m not interested in making a huge amount of money out of this. I do what I do because I’ve got to fucking do it.”

‘three men, in tears’ is published on July 1 by Autopsy,

hartnett.uk.com